Vaccine hesitancy in parents: how can we help?

Dominique Gagnon, MSc, Frédérique Beauchamp, MD Alexandre Bergeron, MD, MSc Eve Dubé, PhD

Dominique Gagnon, MSc1, Frédérique Beauchamp2, MD, Alexandre Bergeron, MD, MSc3, Eve Dubé, PhD4

- Direction des risques biologiques, Institut national de santé publique du Québec

- Faculté de médecine, Université Laval

- Faculté de médecine, Université Laval

- Direction des risques biologiques, Institut national de santé publique du Québec

On July 14, 2022, Canada approved the first COVID-19 vaccine for children aged 6 months to 5 years. However, in Canada and elsewhere, a lower intention among parents to accept COVID-19 vaccination for their children under 5 years of age has been observed(1-3). Vaccine safety is a common concern contributing to a lack of vaccine confidence. In fact, prior to the pandemic, approximately 20% of Canadian parents were concerned about the safety and efficacy of routine childhood vaccines(4). This CANVax in Brief aims to identify some possible interventions to improve parental confidence in routine childhood vaccinations, including COVID-19 vaccines, by using The Behavioural and Social Drivers (BeSD) Vaccination Framework(5).

Determinants of Vaccine Acceptance and Uptake

At this time, it is difficult to assess to what extent the COVID-19 pandemic and COVID-19 vaccination campaigns have impacted parents’ views towards routine vaccines(6). However, concerns about vaccine safety and efficacy as well as online misinformation/disinformation were ubiquitous, especially since the beginning of the COVID-19 vaccine roll-out. The increased polarization of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in Canada can further hamper dialogue between healthcare providers and parents when it comes to discussing routine vaccinations.

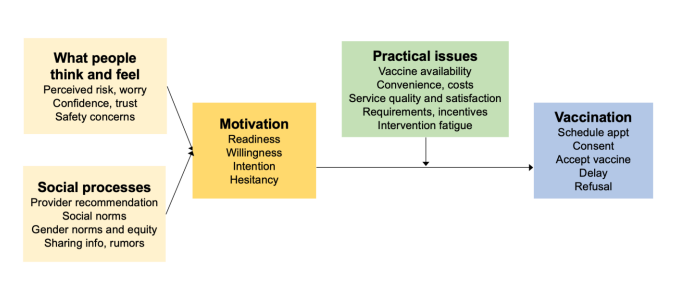

As shown in Figure 1, determinants of vaccine acceptance, hesitancy and refusal are complex and multidimensional; they vary across geographic locations, groups within populations, and types of vaccines. Therefore, it is important to have a good understanding of the determinants of parental perceptions and behaviours regarding vaccines to be able to develop tailored interventions.

Figure 1. The Behavioural and Social Drivers of Vaccination (BeSD) Framework

Source: Brewer NT, Chapman GB, Rothman AJ, Leask J, Kempe A. Increasing Vaccination: Putting Psychological Science Into Action. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2017;18(3):149-207.

What people think and feel

This category refers to parents’ cognitive and emotional responses (such as perceived risk, worry, confidence, trust, and safety issues) that needs to be considered when developing and implementing interventions.

Generally, a large majority of Canadian parents have positive views towards vaccines administered in children(4). Common parental concerns on childhood vaccination identified in the literature revolves around safety, efficacy and the need for vaccination(7). These findings also appear to hold true for COVID-19 vaccination in children, including in the Canadian population(8-10).

Educational and informational strategies are often used to address what people think and feel about vaccines, with varying levels of success in enhancing acceptance and vaccine literacy(11). To increase the effectiveness of such interventions, the use of plain language and everyday terminology, culturally sensitive material, online and offline communication strategies and communication tools available in multiple language are key. (Refer to the CANVax brief, Optimizing communication material to address vaccine hesitancy published in the Canada Communicable Disease Report (CCDR) for more information).

Additionally, special attention should be paid to reaching equity-seeking groups and strategies should be designed to avoid increasing disparities in the understandings of vaccines. Specific to the COVID-19 context and the infodemic of false information about vaccines, pre-bunking1 and debunking interventions to correct vaccine misinformation have shown positive impact on the intention to vaccinate(12). As parents are frequently seeking vaccine information from online sources to inform their decisions, creating awareness around vaccine misinformation on popular social media platforms might increase their ability to value this kind of information.

1Prebunking is based on the inoculation theory and can be explained just as vaccines work: vaccines trigger the production of antibodies by exposing people to a weakened dose of a pathogen and the same can be achieved with information by exposing people to a weakened dose of the techniques used in misinformation. Debunking is the act of providing detailed and clear refutations of false information after people have been exposed to a falsehood. For more information, see The Debunking Handbook 2020.

Social processes

This category refers to social norms about vaccines and vaccination, including recommendations for parents to have their children vaccinated.

Healthcare professionals play a critical role in the success of vaccination programs as their recommendations have a significant impact on parents’ confidence in vaccination and acceptance(7), including for new vaccines such as COVID-19(8). Healthcare professionals are considered a trusted source of information among parents and patients and can often provide them with reassurance about vaccines. Therefore, it is important to support healthcare professionals on vaccination counselling interventions. (Refer to the CANVax brief, Motivational Interviewing: A Powerful Tool for Immunization Dialogue published in the Canada Communicable Disease Report (CCDR) for more information).

Another way to influence social processes around vaccination include promoting positive social norms in order to normalize vaccination. Vaccine champions and advocates in communities can help normalize vaccination through sharing their positive vaccine experiences with others. Partnering with local organizations, religious leaders, and other trusted community voices and health officials might help address issues of trust in health authorities and vaccine confidence in under-vaccinated communities.

Motivation for vaccination

This category refers to the motivations for someone to get vaccinated, which includes the level of intention, willingness, and hesitancy of the person.

For vaccine-hesitant parents, as noted above, the interaction with healthcare professionals remains very effective at promoting vaccine acceptance. Dialogue-based intervention and one-to-one counselling approaches using motivational interviewing techniques can increase vaccine acceptance among parents who are unsure or unwilling to vaccinate their children(12-13).

Practical issues

This category refers to a person’s experiences with past vaccinations. Previous experiences can include barriers in access to vaccination services (such as financial barriers, geographical barriers or appointment availability barriers) as well as systemic/structural barriers in the way vaccination services are delivered.

Many effective interventions to address practical issues with regards to vaccination have been identified in the literature(14, 15):

- reducing out-of-pocket costs of vaccination,

- providing vaccination without appointments or improving appointment scheduling,

- partnering with community organizations that target vulnerable clients to provide vaccination, including vaccination as part of other interventions or medical visits or supporting the offer of vaccines in non-traditional settings (e.g., pharmacies, child care centres).

Administering routinely recommended vaccines to children in school settings remains a promising and accessible way to enhance vaccine uptake(16). It is also important to consider how vaccination services are delivered (i.e. ensuring that the information delivered is culturally adaptable, considering the parent’s level of health literacy when information is delivered, etc.). As highlighted by the pandemic, systemic and structural barriers in healthcare (including racism, discrimination, gender-bias) still exist in Canada, and healthcare providers need to recognize these barriers and try to overcome them when offering vaccination services to their patients in order to ensure equitable access.

Other effective interventions include reminder and recall strategies and other logistics and behavioral defaults, such as automatically scheduled appointments(17). Vaccination incentives and rewards, such as food vouchers, gift cards or baby products have also been shown to be effective in increasing parents’ decision to get their children vaccinated(18).

Conclusion:

In conclusion, we highlighted some evidence-informed interventions to address the different barriers to childhood vaccination. Table 1 summarizes these interventions with examples from Canadian vaccination initiatives and resources. It is well-recognized that multicomponent interventions, that address two or more of these factors are likely to be more effective in increasing vaccine acceptance and uptake(19). Furthermore, a good understanding of the factors that influence parental vaccination decisions (i.e. measuring parents’ thinking and feeling, social processes, motivations and practical issues) at the local level is key to developing tailored interventions. (Refer to the CANVax brief, Designing tailored interventions to address barriers to vaccination published in the Canada Communicable Disease Report (CCDR) for more information). Building and maintaining vaccine confidence is an ongoing and long-term task(20), especially as the COVID-19 pandemic and vaccine roll-out may have made parents more hesitant about vaccines in general. In this context, ensuring a high level of childhood vaccine acceptance may require greater efforts to avoid future outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases.

Table 1. The Behavioural and Social Drivers of Vaccination (BeSD) framework and interventions to improve vaccination in children (including COVID-19 vaccines)

| Domain of the BeSD | Types of interventions that can increase vaccination | Examples in Canada |

|---|---|---|

| Thinking and feeling How can we react to parents’ cognitive and emotional responses to vaccine-preventable diseases and vaccines |

|

A parents’ guide to vaccination (available in 14 languages) Max the Vax, a campaign providing education tools for children and parents in Ontario |

| Social processes How can we positively promote and recommend vaccination? |

|

Protect our People, a campaign promoting vaccination to Indigenous peoples in Manitoba |

| Motivation How can we act on parents’ intention to get their children vaccinated? |

|

MIICOVAC, a research project that allow vaccine hesitant individuals to meeting with trained immunization counsellors about COVID-19 vaccination |

| Practical issues How can we facilitate access and reduce barriers to vaccination? |

|

GO-VAXX, buses and mobile indoor vaccine clinics providing COVID-19 vaccines in Ontario |

References:

- Fisher CB, Bragard E, Jaber R, Gray A. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy among Parents of Children under Five Years in the United States. Vaccines (Basel). 2022;10(8).

- Humble RM, Sell H, Wilson S, Sadarangani M, Bettinger JA, Meyer SB, et al. Parents' perceptions on COVID-19 vaccination as the new routine for their children ≤ 11 years old. Prev Med. 2022;161:107125.

- Scherer AM, Gidengil CA, Gedlinske AM, Parker AM, Askelson NM, Woodworth KR, et al. COVID-19 Vaccination Intentions, Concerns, and Facilitators Among US Parents of Children Ages 6 Months Through 4 Years. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(8):e2227437.

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Vaccine Hesitancy in Canadian Parents. 2022.

- World Health Organization. Behavioural and social drivers of vaccination: tools and practical guidance for achieving high uptake: World Health Organization; 2022 [Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/354459].

- He K, Mack WJ, Neely M, Lewis L, Anand V. Parental Perspectives on Immunizations: Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Childhood Vaccine Hesitancy. J Community Health. 2022;47(1):39-52.

- McGregor S, Goldman RD. Determinants of parental vaccine hesitancy. Can Fam Physician. 2021;67(5):339-41.

- Galanis P, Vraka I, Siskou O, Konstantakopoulou O, Katsiroumpa A, Kaitelidou D. Willingness, refusal and influential factors of parents to vaccinate their children against the COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med. 2022;157:106994.

- Dubé E, Gagnon D, Pelletier C. COVID-19 vaccination in 5-11 years old children: Drivers of vaccine hesitancy among parents in Quebec. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2022;18(1):2028516.

- Humble RM, Sell H, Dubé E, MacDonald NE, Robinson J, Driedger SM, et al. Canadian parents' perceptions of COVID-19 vaccination and intention to vaccinate their children: Results from a cross-sectional national survey. Vaccine. 2021;39(52):7669-76.

- Dubé E, Gagnon D, MacDonald NE. Strategies intended to address vaccine hesitancy: Review of published reviews. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4191-203.

- MacDonald NE, Comeau J, Dubé È, Graham J, Greenwood M, Harmon S, et al. Royal society of Canada COVID-19 report: Enhancing COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in Canada. FACETS. 2021;6:1184-246.

- Gagneur A. Motivational interviewing: A powerful tool to address vaccine hesitancy. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2020;46(4):93-7.

- Community Preventive Service Task Force. Vaccination Programs: Schools and Organized Child Care Centers. 2009 [cited 2022 August 31]. Available from: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/vaccination-programs-schools-and-organized-child-care-centers.

- Community Preventive Service Task Force. Vaccination Programs: Reducing Client Out-of-Pocket Costs. 2014 [cited 2022 August 31]. Available from: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/vaccination-programs-reducing-client-out-pocket-costs.

- Perman S, Turner S, Ramsay AI, Baim-Lance A, Utley M, Fulop NJ. School-based vaccination programmes: a systematic review of the evidence on organisation and delivery in high income countries. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):252.

- Community Preventive Service Task Force. Vaccination Programs: Client Reminder and Recall Systems. 2015 [cited 2022 August 31]. Available from: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/vaccination-programs-client-reminder-and-recall-systems.

- Community Preventive Service Task Force. Vaccination Programs: Client or Family Incentive Rewards. 2015 [cited 2022 June 20]. Available from: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/vaccination-programs-client-or-family-incentive-rewards.

- Jarrett C, Wilson R, O'Leary M, Eckersberger E, Larson HJ. Strategies for addressing vaccine hesitancy - A systematic review. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4180-90.

- Sondagar C, Xu R, MacDonald NE, Dubé E. Vaccine acceptance: How to build and maintain trust in immunization. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2020;46(5):155-9.