Overview of Canadian School-Based Immunization Programs

Kodzo Awoenam Adedzi, Eve Dubé

Kodzo Awoenam Adedzi, Institut national de santé publique du Québec, Québec (Québec)

Ève Dubé, Institut national de santé publique du Québec, Québec (Québec)

School-based immunization programs are implemented in all Canadian provinces and territories. These programs are an effective and equitable approach to reach and vaccinate children and teenagers, and can reduce the prevalence of many infectious diseases. This CANVax in Brief presents an overview of school-based immunization programs in Canada, the benefits and challenges of school-based vaccination, and ways to optimize these programs.

In Canada, despite the success of immunization programs in reducing the prevalence of vaccine-preventable diseases, outbreaks still occur occasionally in unvaccinated and geographically clustered communities. For example, in 1989, major measles outbreaks occurred in different Canadian jurisdictions (1–4). The origin of these school-based immunization programs can be traced back to when community immunization programs were first implemented, where measles outbreaks acted as the catalyst in the implementation of vaccination programs in schools (4). Currently, all provinces and territories provide vaccines in primary and secondary schools. In this CANVax in Brief, we will provide an overview of Canadian school-based immunization programs, including the benefits, the specific challenges, and ways to optimize these programs.

1 For a complete history of vaccination in Canada, please visit the Canadian Public Health Association website (https://www.cpha.ca/immunization-timeline).

School-Based Immunization Programs in Canada

School-based immunization programs in Canada can be defined as the routine administration of vaccines in schools – this excludes vaccinations carried out during community or mass campaigns (5). As they are health care services, vaccination programs are a provincial/territorial (P/T) responsibility.

Information on immunizations provided in school settings is available on P/T government websites, as well as in a full immunization schedule format offered by the Public Health Agency of Canada , updated on a quarterly basis by the Canadian Nursing Coalition for Immunization (CNCI) (Table 1). School immunization programs can differ from jurisdiction to jurisdiction (5). At present, three provinces (Ontario, New Brunswick, and Manitoba) have strengthened their school immunization policies through legislation that applies strictly to school-age children. Ontario and New Brunswick require proof of vaccination prior to school entry against several diseases , whereas Manitoba requires only proof of vaccination against measles (5). The laws in each of these three provinces include a clause that allows parents to exempt their children from being vaccinated for medical or religious/philosophical reasons. However, in the event of an outbreak, unvaccinated children may not be allowed to attend school

2 Since its first publication in 1979, the Canadian Immunization Guide has provided a summary of recommendations from the National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI.

3 Proof of immunization against diphtheria, tetanus, polio, pertussis, measles, mumps, rubella, meningococcal disease (meningitis), varicella (chickenpox) (only in Ontario - required for children born in 2010 or later) is required in both Ontario and New Brunswick.

Table 1. School-Based Immunization Programs in Canada

| Province or Territory | Program name | Vaccine coverage | Link |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alberta | Alberta Health Services: Immunization |

|

https://immunizealberta.ca/i-want-immunize/when-immunize |

| British Columbia |

B.C. Immunization Schedules |

|

https://www.healthlinkbc.ca/tools-videos/bc-immunization-schedules#school |

| Manitoba | Health, Seniors and Active Living |

|

https://www.gov.mb.ca/health/publichealth/cdc/div/schedules.html |

| New Brunswick | Office of the Chief Medical Officer of Health (Public Health): Immunization Program Guide |

|

https://www2.gnb.ca/content/gnb/en/departments/ocmoh/for_healthprofessionals/cdc/NBImmunizationGuide.html |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | Health and Community Services |

|

https://www.health.gov.nl.ca/health/publichealth/cdc/immunizations.html |

| Northwest Territories | Immunization/Vaccination |

|

https://www.hss.gov.nt.ca/en/services/immunization-vaccination |

| Nova Scotia | Routine Immunization Schedules for Children, Youth and Adults |

|

https://novascotia.ca/dhw/cdpc/immunization.asp |

| Nunavut | Nunavut Recommended Childhood Immunization Schedule |

|

https://www.gov.nu.ca/health/information/immunization |

| Ontario | Vaccines for children at school |

|

https://www.ontario.ca/page/vaccines-children-school |

| Prince Edward Island | Immunization Program |

|

https://www.princeedwardisland.ca/en/information/health-and-wellness/childhood-immunizations |

| Québec | Immunization schedule for school-age children |

|

https://www.quebec.ca/en/health/advice-and-prevention/vaccination/quebec-immunisation-program/#c24030 |

| Saskatchewan | Immunization Services |

|

https://www.saskatchewan.ca/residents/health/accessing-health-care-services/immunization-services |

| Yukon | Yukon Immunize |

|

http://www.yukonimmunization.ca/diseases-vaccines/grade-6-9-school-based-immunization |

- Note:

HPV: Human papillomavirus vaccine

Men-C-C: Meningococcal conjugate (Strain C) vaccine

Men-C-ACYW-135: Meningococcal conjugate (Strains A, C, Y, W135) vaccine

Tdap: Tetanus, diphtheria (reduced toxoid), acellular pertussis (reduced toxoid), vaccine

Evaluation of the Effectiveness of School-Based Immunization Programs

A systematic review showed that school-based immunization programs are an effective and cost-efficient approach to enhance vaccine uptake rates (6). Vaccination uptake rates with school-based programs are higher for school-age children than strategies involving home visits and combined community strategies, which are both more costly and less effective.

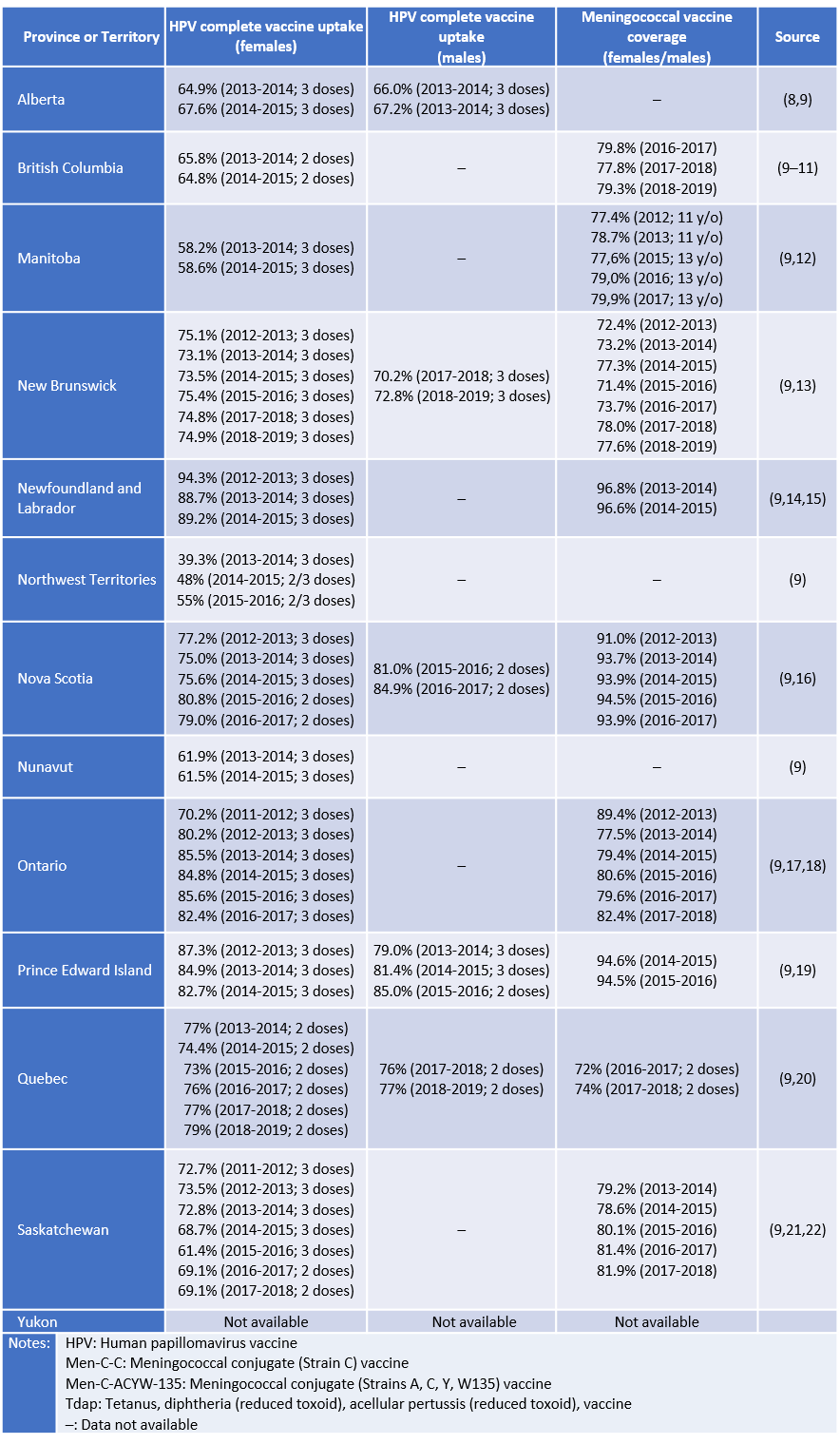

Table 2 presents HPV and meningococcal vaccine uptake rates achieved in Canadian school-based immunization programs. The coverage rates presented in the table are below the public health goals of vaccinating 90% of target groups in multiple jurisdictions (7). There are substantial variations between and within Canadian P/Ts.

Table 2. School-Based Immunization Programs in Canada: HPV Vaccination Completion Rates and Meningococcal Vaccination Coverage Rates for Different Canadian Jurisdictions

Even with these suboptimal vaccine uptake rates, in the case of HPV vaccination, studies have shown that school-based immunization programs have higher vaccination rates in countries such as Canada, Spain, Scotland and Australia (23,24). Clearly, school-based immunization programs cover school-age children better than community-based immunization programs. Also, school-based vaccination can help reduce socio-economic inequalities in vaccine distribution (24). As the vast majority of children below the age of 14 are attending schools in Canada, delivering immunization in schools has the potential to reduce inequalities in access to health services based on socio-economic factors (25).

Key Issues Related to School-Based Immunization Programs

Perman and colleagues have identified eight factors that hinder school-based immunization programs (26):

- National and regional policy issues.

- Program management and direction.

- Organizational models and institutional relationships.

- The facilities and systems required to operate the programs, such as data entry, distribution, and vaccine supply systems.

- The labour force (often mentioned in studies from different countries), which experiences recurring issues such as staff capacity, workload, skill mix, years of experience and job roles.

- The financing, billing, reimbursement and sustainability issues of the program.

- Regardless of the country or type of vaccine, communicating to parents the purpose of vaccination and obtaining parental consent is reported to be one of the most important factors in the proper functioning of the program.

- Clinical organization and performance. This includes logistics and the physical configuration of clinics to facilitate the flow of students. Most of the studies that focused on this factor were American articles on pandemic and seasonal influenza.

Another issue with school-based immunization programs is the attitude of the parents or the students themselves. MacDougall and colleagues interviewed 55 Ontario parents who had already vaccinated at least one child against influenza or who had never done so between October 2012 and February 2013 (27). Although the majority of participants found the programs useful for school-age children, most parents felt that in order for a program to be acceptable, it should be well designed, with adequate parental control and transparent communication between the key parties involved. The main barrier to school-based immunization programs identified by parents, nurses, teachers, and managers interviewed in an evaluation of school-based HPV vaccination programs was the negative impact of misinformation from the Internet and social networks, which creates doubts about vaccination (27).

The challenge of obtaining consent is another issue in school-based vaccination. Health professionals are not always clear about how best to manage the consent process in a context where 14-year-olds can consent in some jurisdictions and cannot consent in other jurisdictions (28). A more rigorous evaluation of interventions could improve the consent process in school-based immunization programs. Recommendations to help address this gap include developing vaccinology training and education programs for medical and other health students, teaching about vaccines in schools, and using motivational interviewing techniques as an educational intervention for parents who have children in school (29).

In Canada, using the example of HPV, potential adverse events after immunization (AEFIs) associated with the HPV vaccine are generally communicated on paper, along with informed consent forms to parents, legal guardians and students. However, the information about the nature and the probabilities of AEFIs as presented in these medic-legal documents differ from one P/T to another (30). If risks are not presented in a comprehensive and consistent way across Canadian provinces and territories, then there is a chance of communicating inaccurate, incomplete and inconsistent information that may negatively affect the consent process (30). Braunack-Mayer and colleagues identified the ethical challenges associated with the process and divided them into three categories (31). The first category is informed consent, which considers how the information for students is communicated, along with the decision-making capacity and voluntariness of students, especially since there are limits to how much accommodation can be offered for informed consent. The second category is the importance of privacy and confidentiality, and the third category is the negative effect of fear and anxiety. According to the authors of this study, some of these challenges can be overcome by adopting the same strategies used for vaccinations in a private setting (31), for example, the use of evidence-based interventions to reduce fear and anxiety during immunization (32).

Potential interventions to enhance vaccine acceptance and uptake in school-based immunization programs

Offering vaccination in school-based settings is recognized as an effective strategy to increase vaccination uptake rates (6), but other interventions can also be implemented in schools to further enhance vaccine acceptance and uptake. The use of a reminder and recall system is highly effective when used for immunizations given in school settings (6). Other promising interventions are currently being tested in Canadian school-based programs. For example, Tozzi and colleagues have emphasized the effectiveness of technological tools in improving immunization programs (33). A example of a technological intervention implemented in Canada is the Kids Boost Immunity (KBI) platform (34). KBI’s website offers accurate, up-to-date, and well-documented information on immunization for students and teachers, as well as online quizzes to increase users’ vaccination knowledge. Quizzes allow students to learn about vaccines while having fun and doing a good deed (based on the number of correct answers, vaccines are donated to developing countries in collaboration with UNICEF). By informing and educating children about vaccines, it is possible to improve their motivation to be vaccinated in the present and should they later become parents. The impact of KBI on vaccine acceptability has not yet been evaluated, but educational strategies such as the promotion of exercise and environmental protection have been shown to be effective in changing behaviours (35,36).

A second potential intervention aims to address pain and needle fear during vaccination. Many children are afraid of needles and pain, and this fear can lead to vaccine refusal in the context of school vaccination (37). However, the use of evidence-based interventions to reduce pain and anxiety during immunization has not been widely implemented in school-based programs (38). A multifaceted knowledge translation strategy called the CARD™ system (Comfort, Ask, Relax, Distract) was developed by Taddio and colleagues to address this gap (38). The CARD™ system is integrated in school-based immunization programs and is focused on pre-vaccination day preparation (e.g., planning of clinic spaces, education for student and school staff) and vaccination day activities (e.g., implementing CARD™ interventions to reduce pain, fear and fainting). It also includes tools for students, school nurses and parents (39). Preliminary results from the controlled clinical trial have shown that the CARD™ system has had a positive impact on students’ attitudes, knowledge, coping strategies used, and symptoms during school-based vaccinations (38).

Conclusion

School-based immunization programs are a very effective and equitable way to reach and vaccinate children and adolescents. There is strong evidence that delivering vaccines in schools can achieve higher vaccine uptake rates than other strategies based in health facilities (6). All Canadian provinces and territories have implemented routine vaccination in schools, but vaccine uptake rates remain suboptimal in some jurisdictions, especially in the case of the HPV vaccine. Reminder and recall systems, education interventions such as KBI, and interventions to reduce pain and anxiety during vaccination such as the CARD™ system could be implemented widely in schools to further enhance vaccine acceptance and uptake.

References

- Naus M, Puddicombe D, Murti M, Fung C, Stam R, Loadman S, et al. Outbreak of measles in an unvaccinated population, British Columbia, 2014. Can Commun Dis Rep Releve Mal Transm Au Can. 2015 Jul 2;41(7):169–74.

- BC Centre for Disease Control. Measles Outbreak - Fraser Health Region [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2019 Oct 25]. Available from: http://www.bccdc.ca/about/news-stories/news-releases/2014/measles-outbreak-fraser-health-region

- Sherrard L, Hiebert J, Squires S. Measles surveillance in Canada: Trends for 2014. Can Commun Dis Rep Releve Mal Transm Au Can. 2015;41(7):157–68.

- Monnais L. Vaccinations : le mythe du refus [Internet]. Presses de l’Université de Montréal; 2019. Available from: https://www.pum.umontreal.ca/catalogue/vaccinations

- Government of Canada. Provincial and territorial routine and catch-up vaccination schedule for infants and children in Canada [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Oct 29]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/provincial-territorial-immunization-information/provincial-territorial-routine-vaccination-programs-infants-children.html

- Jacob V, Chattopadhyay SK, Hopkins DP, Murphy Morgan J, Pitan AA, Clymer JM, et al. Increasing Coverage of Appropriate Vaccinations: A Community Guide Systematic Economic Review. Am J Prev Med. 2016/02/01. 2016 Jun;50(6):797–808.

- Government of Canada. Vaccination Coverage Goals and Vaccine Preventable Disease Reduction Targets by 2025 [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2020 Apr 17]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/immunization-vaccine-priorities/national-immunization-strategy/vaccination-coverage-goals-vaccine-preventable-diseases-reduction-targets-2025.html#1.0

- Alberta Health Services. Alberta Health Services Annual Report 2017-18 [Internet]. 2018. Available from: https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/about/publications/2017-18-annual-report-web-version.pdf

- Shapiro GK, Guichon J, Kelaher M. Canadian school-based HPV vaccine programs and policy considerations. Vaccine. 2017 Oct 9;35(42):5700–7.

- BC Centre for Disease Control. Immunization Uptake in Grade 6 Students (2019) [Internet]. Vancouver, BC; 2019. Available from: http://www.bccdc.ca/resource-gallery/Documents/Statistics%20and%20Research/Statistics%20and%20Reports/Immunization/Coverage/Grade%206%20Coverage%20Results.pdf

- BC Centre for Disease Control. Immunization Uptake in Grade 9 Students (2019) [Internet]. Vancouver, BC; 2019. Available from: http://www.bccdc.ca/resource-gallery/Documents/Statistics%20and%20Research/Statistics%20and%20Reports/Immunization/Coverage/Grade%209%20Coverage%20Results.pdf

- Manitoba Health, Seniors and Active Living. Annual Report of Immunization Surveillance. Public Health Information Management System (PHIMS) [Internet]. [cited 2020 Apr 10]. Available from: https://www.gov.mb.ca/health/publichealth/surveillance/immunization/index.html

- Government of New Brunswick. Communicable Disease Control: Immunization reports [Internet]. New Brunswick: Office of the Chief Medical Officer of Health (Public Health); [cited 2020 Apr 10]. Available from: https://www2.gnb.ca/content/gnb/en/departments/ocmoh/for_healthprofessionals/cdc.html

- Government of Newfoundland and Labrador. Communicable Disease Report. Quarterly Report [Internet]. 2015 Dec. Volume 32, Number 4. Available from: https://www.health.gov.nl.ca/health/publichealth/cdc/pdf/CDR_Dec_2015_Vol_32.pdf

- Government of Newfoundland and Labrador. Communicable Disease Report. Quarterly Report [Internet]. 2015 Mar. Volume 32, Number 1. Available from: https://www.health.gov.nl.ca/health/publichealth/cdc/CDR_March_2015_Vol_32_No_1.pdf

- Government of Nova Scotia. Population Health Assessment and Surveillance [Internet]. [cited 2020 Apr 10]. Available from: https://novascotia.ca/dhw/populationhealth/

- Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion (Public Health Ontario). Immunization coverage report for school pupils: 2013–14, 2014–15 and 2015–16 school years [Internet]. Toronto, ON: Queen’s Printer for Ontario; 2017. Available from: https://www.publichealthontario.ca/-/media/documents/immunization-coverage-2013-16.pdf?la=en

- Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion (Public Health Ontario). Immunization coverage report for school pupils in Ontario: 2016–17 school year [Internet]. Toronto, ON: Queen’s Printer for Ontario; 2018. Available from: https://www.publichealthontario.ca/-/media/documents/immunization-coverage-2016-17.pdf?la=en

- Prince Edward Island Provincial Immunization Committee Chief Public Health Office. Childhood Immunization in PEI. Prince Edward Island Childhood Immunization Program [Internet]. Prince Edward Island; 2017. Available from: https://www.princeedwardisland.ca/sites/default/files/publications/childhoodreportfinal.pdf

- Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux. Flash Vigie - Bulletin québécois de vigie, de surveillance et d’intervention en protection de la santé publique [Internet]. [cited 2020 Mar 9]. Available from: https://publications.msss.gouv.qc.ca/msss/document-000052/?&txt=Flash%20Vigie&msss_valpub&date=DESC

- Population Health Branch, Saskatchewan Ministry of Health. Vaccine Preventable Disease Monitoring Report. Human Papillomavirus, 2017 and 2018 [Internet]. 2019. Available from: https://publications.saskatchewan.ca/api/v1/products/101145/formats/111773/download

- Population Health Branch, Saskatchewan Ministry of Health. Vaccine Preventable Disease Monitoring Report. Meningococcal, 2017 and 2018 [Internet]. 2019. Available from: https://publications.saskatchewan.ca/api/v1/products/101910/formats/112734/download

- Bird Y, Obidiya O, Mahmood R, Nwankwo C, Moraros J. Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Uptake in Canada: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Int J Prev Med. 2017;8(71):1–9.

- Hopkins TG, Wood N. Female human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination: Global uptake and the impact of attitudes. Vaccine. 2013 Mar 25;31(13):1673–9.

- Boyce T, Gudorf A, de Kat C, Muscat M, Butler R, Habersaat KB. Towards equity in immunisation. Euro Surveill Bull Eur Sur Mal Transm Eur Commun Dis Bull. 2019 Jan;24(2):1800204.

- Perman S, Turner S, Ramsay AI, Baim-Lance A, Utley M, Fulop NJ. School-based vaccination programmes: a systematic review of the evidence on organisation and delivery in high income countries. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):252.

- MacDougall D, Crowe L, Pereira JA, Kwong JC, Quach S, Wormsbecker AE, et al. Parental perceptions of school-based influenza immunisation in Ontario, Canada: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2014;4(6):e005189.

- Chantler T, Letley L, Paterson P, Yarwood J, Saliba V, Mounier-Jack S. Optimising informed consent in school-based adolescent vaccination programmes in England: A multiple methods analysis. Vaccine. 2019 Aug 23;37(36):5218–24.

- Dutilleul A, Morel J, Shilte C, Launay O, Autran B, Béhier J-M, et al. Comment améliorer l’acceptabilité vaccinale (évaluation, pharmacovigilance, communication, santé publique, obligation vaccinale, peurs et croyances). Thérapie. 2019;74(1):119–29.

- Steenbeek A, MacDonald N, Downie J, Appleton M, Baylis F. Ill-Informed Consent? A Content Analysis of Physical Risk Disclosure in School-Based HPV Vaccine Programs. Public Health Nurs. 2012;29(1):71–9.

- Braunack-Mayer A, Skinner SR, Collins J, Tooher R, Proeve C, O’Keefe M, et al. Ethical Challenges in School-Based Immunization Programs for Adolescents: A Qualitative Study. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(7):1399–403.

- Schechter NL, Zempsky WT, Cohen LL, McGrath PJ, McMurtry CM, Bright NS. Pain Reduction During Pediatric Immunizations: Evidence-Based Review and Recommendations. Pediatrics. 2007 May 1;119(5):e1184.

- Tozzi AE, Gesualdo F, D’Ambrosio A, Pandolfi E, Agricola E, Lopalco P. Can Digital Tools Be Used for Improving Immunization Programs? Front Public Health. 2016 Mar;4(36).

- Public Health Association of BC. Free Science, Social Studies and Health lessons developed by teachers to inspire digital-age students in support of UNICEF Canada! [Internet]. Kids Boost Immunity. 2020 [cited 2020 Apr 17]. Available from: https://kidsboostimmunity.com/

- Laine J, Kuvaja-Köllner V, Pietilä E, Koivuneva M, Valtonen H, Kankaanpää E. Cost-Effectiveness of Population-Level Physical Activity Interventions: A Systematic Review. Am J Health Promot. 2014 Nov 1;29(2):71–80.

- Wysession M, Taber J, Budd DA, Campbell K, Conklin M, LaDue N, et al. Earth Science Literacy: The Big Ideas and Supporting Concepts of Earth Science [Internet]. National Science Foundation; 2010. Available from: http://www.earthscienceliteracy.org/es_literacy_6may10_.pdf

- McMurtry CM, Pillai Riddell R, Taddio A, Racine N, Asmundson GJG, Noel M, et al. Far From ‘Just a Poke’: Common Painful Needle Procedures and the Development of Needle Fear. Clin J Pain. 2015 Oct;31(10 Suppl):S3–11.

- Freedman T, Taddio A, Alderman L, McDowall T, deVlaming-Kot C, McMurtry CM, et al. The CARDTM System for improving the vaccination experience at school: Results of a small-scale implementation project on student symptoms. Paediatr Child Health. 2019;24(Supplement_1):S42–53.

- Taddio A. Effectiveness of CARD for Improving School-Based Immunizations [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2020 Apr 17]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03966391